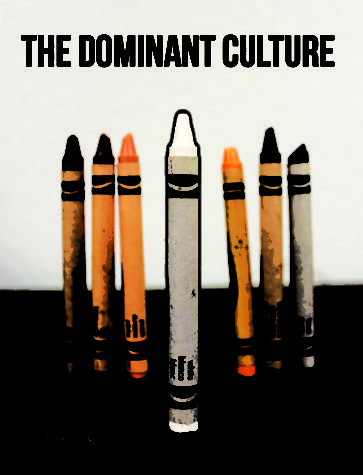

Racial slurs cause frustration for minorities

Senior Kennedy Buchanan was in elementary school when she first realized that the color of her skin separated her from her classmates in her overwhelmingly white school. Buchanan sat confused as she attempted to understand her peer’s question.

“Do you like being black, or would you rather be white?”

Buchanan could only respond with silence. As an 8-year-old, she hadn’t realized that her peers saw her as unlike themselves, or that they saw being black as unfavorable. As she looked around, she noticed she could count the number of other black students on one hand.

“It was just kind of confusing not seeing people who looked like me all throughout elementary school,” Buchanan said.

As Buchanan approached high school, she remained one of the few black students in her classes. She continued to hear comments like “you’re articulate for a black girl.” Although she knew her peers didn’t mean to insult her, words like these triggered a pang of frustration. They served as a reminder that many of her peers maintained stereotypes about black people.

I like to say when people use that language, ‘please don’t use that language around me’.

— Kennedy Buchanan

Despite the lack of black students at the school, black artists started growing in popularity. Not only did hip hop style appeal to her peers, but their language did as well. Buchanan would remain quiet as her peers, including her friends, would toss around variations of “n****r” as if it was a lighthearted colloquialism rather than a word surrounded by a painful history.

As Buchanan’s friends and classmates quoted song lyrics and attempted to mimic black culture, she didn’t feel like it was her place to make them aware of the impact of their words. Buchanan said that because they were her friends, they felt comfortable using this racially charged language around her, as if they saw her as less black than the artists who created the music.

“I didn’t know what was right, what was wrong,” Buchanan said. “I was not confident enough to say something about it.”

Buchanan remembers a time when a friend used “n****r”. This time when she voiced her concerns, she was met with backlash from others. They didn’t understand why she took it so seriously. She said those who disagreed with her did not understand the full impact of using slurs, even as a joke.

“I like to say when people use that language, ‘please don’t use that language around me’,” Buchanan said. “I will say, ‘I don’t use it around you because I don’t want you to use it around me.’”

• • •

Senior Chris Mendonca was in middle school when she first heard the word “gook.” What was an ordinary argument quickly became confusing when her peer hurled the insult at her. The word continued to weigh on her mind. When she asked her mom about it later that day, her mom became furious. She explained that it was a slur used to demean southeast Asian people, especially during the Vietnam war. The outdated insult caused a new insecurity in Mendonca. She said ever since then, she is more aware of how people treat each other.

“That made me more open-eyed to my environment and the type of things people would say to me from then on,” Mendonca said.

Mendonca said that more needs to be done so students can be sensitive to other races and cultures. Mendonca said that it is important for students to make an active effort to become more socially conscious.

“I think if they decide to learn, and they try and get past those racist stereotypes or racist things that they grew up with or learned, then they’re not racist,” Mendonca said. “They’re someone who’s working on themselves.”

• • •

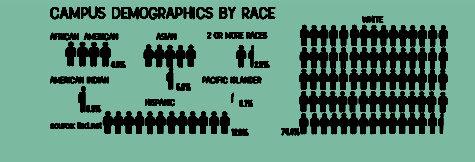

Buchanan said that her peer’s comments are not blatant racism, but a result of the largely white student body. She said that because of the lack of diversity, students are unable to fully understand other cultures.

“To be ignorant you, can still say racist things that are wrong, but I don’t think that they truly dislike certain groups of people,” Buchanan said. “And I think that people who are ignorant may not be fully aware of how their actions affect other people.”

Buchanan says that students may not realize what certain things mean or how their actions affect others and they “say racist things that are wrong, but I don’t think that they truly dislike and have a hatred for certain groups of people.”

Mendonca said she agrees. She said that to understand others’ perspectives, students have to open to learning.

“I think that white students shouldn’t be so offended if someone points something out to them that’s being racist,” Mendonca said. “If what you’re doing is offensive and a student of color says, ‘Hey, this makes me uncomfortable,’ don’t put up a fight. Do more research on it or ask around and see if what you’re doing is offensive.”

My name is Sanika Sule and I am the Editor in Chief. I am a senior and this is my third year on staff. I enjoy watching movies and volunteering at the...